- Home

- ...

- Smarter Targeting of Erosion Control (STEC)

- Smarter Targeting of Erosion Control (STEC) News

Valuing the effect of soil erosion on productivity

In New Zealand, efforts to assess the costs and benefits of erosion mitigation measures are limited by a dearth of benefit estimates and spatially explicit cost data. To date, there are only limited New Zealand-based studies that have attempted to monetise the adverse effects of erosion, and none of them have estimated the impact of erosion on agricultural production. Our study aims to fill this gap and show how these losses could differ across the landscape. The analysis focuses on the Fordell-Kakatahi area, located in the south of Wanganui district, which is a part of the Manawatū-Whanganui region. Estimated impacts were obtained by integrating spatial information on soil erosion rates, erosion-related productivity losses, and farm income. Our results include an estimate of the marginal cost of surficial (overland) and mass movement erosion individually as well as the aggregated marginal cost of erosion.

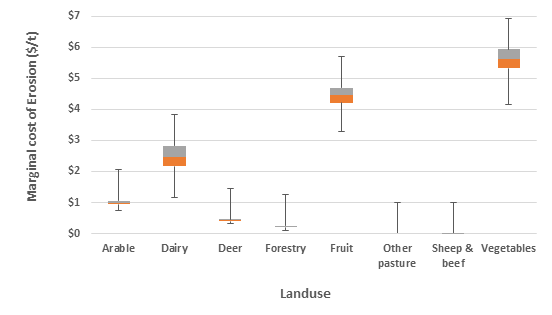

Our results showed that the marginal cost of erosion (in terms of negative impact on productivity) ranges between $0.03 and $5.61 per tonne, with a mean value of $1.8 per tonne, depending on land use. The highest marginal cost of aggregated erosion was experienced in vegetables, fruit, and dairy land uses, while the lowest marginal cost of aggregated erosion was experienced in exotic forestry, sheep and beef, and other pasture land uses. The high erosion cost for horticulture is mainly driven by the high annual net revenues (7–9k/ha). Sheep & beef, and exotic forestry are often located in marginal land with relatively low annual net revenues, and therefore the marginal impact of erosion was lower. For the Fordell-Kakatahi area, the per hectare annual net revenues for sheep & beef was estimated at approximately $8, with exotic forestry estimated at $600 (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Marginal cost of erosion by landuse ($/t)

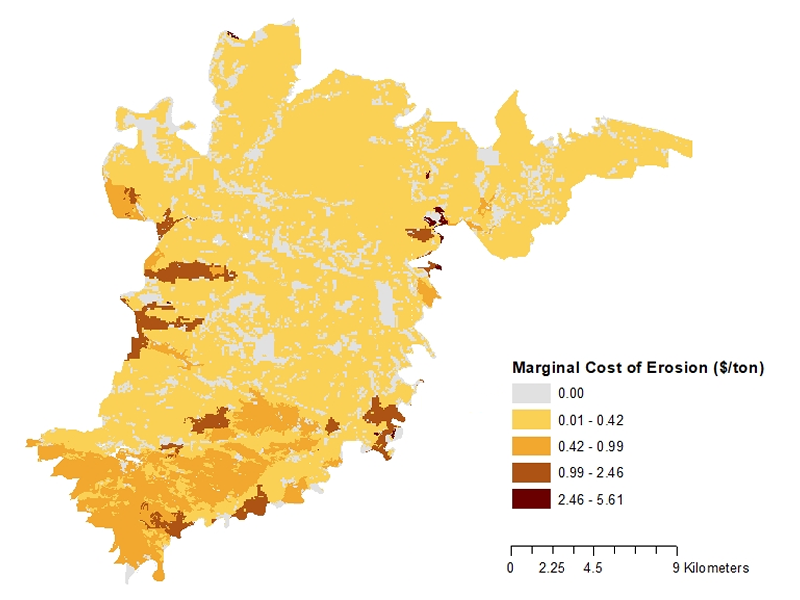

For some land uses, such as sheep and beef, the marginal cost of surficial erosion was higher than the marginal cost of mass movement erosion. This is because many sheep and beef farms are in steeply sloped land and often experience large amounts of eroded soil from mass movement processes. As we assume quite similar productivity damage rates for both types of erosion, this assumption, alongside the high eroded soil rates from mass movement, resulted in lower marginal costs for mass movement erosion compared with surficial erosion. On the other hand, the marginal cost of surficial erosion for dairy farms was lower than the marginal cost of mass movement erosion because dairy farms are located on flat land and therefore experience high surficial erosion and low mass movement erosion. High amounts of surficial erosion mean the estimated marginal cost of surficial erosion was low (Fig. 2). Note that grey areas in the figure denote non-agricultural land and native forest, where there are no productivity impacts (although there are likely other erosion control benefits in those areas).

Figure 2. The spatial distribution of the marginal cost of erosion ($/tonne)

Erosion is a significant problem across New Zealand, and new methods and policies are being developed to combat it. To be able to evaluate those policies properly in a spatially explicit fashion, it is important to value all the relevant impacts. This case study illustrates methods for valuing agricultural productivity-related impacts. The outputs showed that the marginal cost of erosion depends primarily on the profitability of the land use and is adversely correlated with the amount of erosion. Although these results are particular to the profits and erosion rates in this case study area, it can be replicated in other areas. If widely deployed, they can help illuminate significant trade-offs in a cost-benefit decision framework. However, it is important to note potential information gaps and areas of future research. These estimates are dependent on existing research on productivity impacts, as well as on the quality of erosion and land use data. These impacts can also be used in coordination with other benefit and cost estimates currently under development in the STEC programme. For example, new stated preference survey estimates are available to estimate water quality benefits, and Earthquake commission data have been used to analyse the impact of erosion on property damage.