Major expansion of S-map coverage in Taranaki

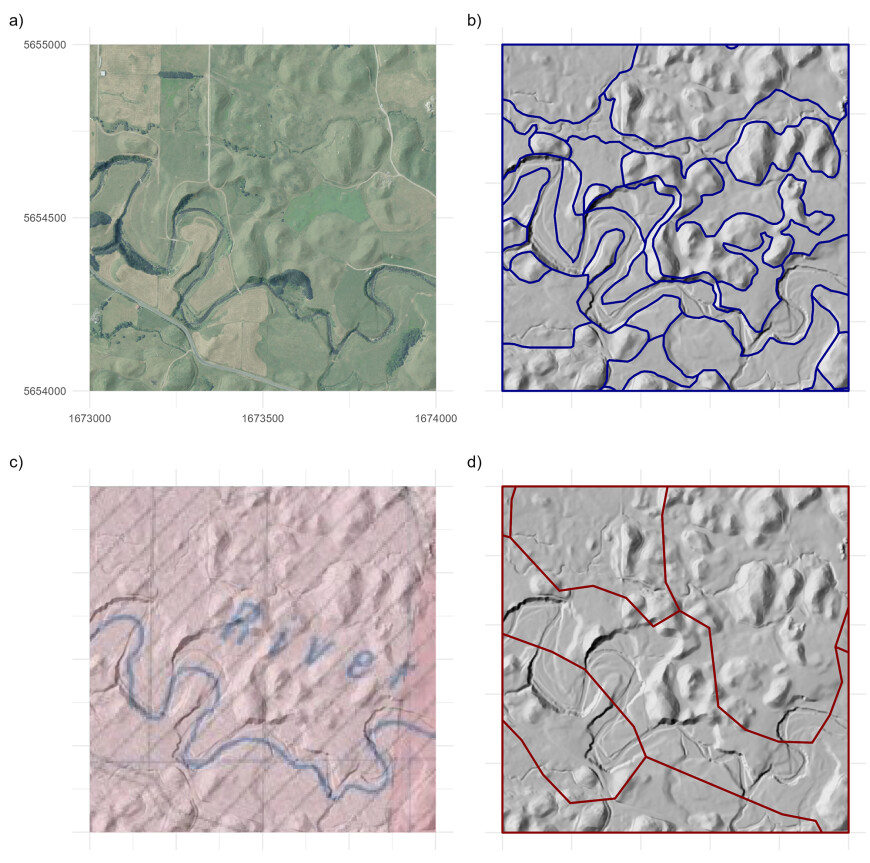

Mapping was completed during 2022–2025 and involved visiting 47 farms and numerous roadside locations, describing 653 new soil profiles, and analysing 426 samples. New field data were combined with existing soil information and secondary supporting data sets, such as detailed LiDAR elevation, allowing new map unit boundaries to be defined with high accuracy and detail. Figure 1 shows a comparison of new map unit boundaries compared with previously available mapping.

Figure 1. A comparison of available map unit boundaries across a 1 × 1 km area along the Te Ikapārua River: (a) satellite imagery showing the river and surrounding terrain; (b) new S-map units, separating areas of debris-avalanche mounds from intermound flats, river terraces, and the main river channel; (c) soils of Egmont and part Taranaki counties (Palmer et al. 1981), showing useful topographic annotation but only two broad units with a tentative boundary; (d) the Fundamental Soils Layer (Landcare Research 1999), showing lower spatial detail and unit boundaries misaligned against the terrain.

Soil landscapes

On the eastern ring plain, closer to Taranaki Maunga, shallow debris-avalanche flow deposits create a drainage barrier beneath more recent tephras. These deposits comprise coarse andesite sands and gravels, which can be lightly welded in places. Overlying cover can be very stony, but most landholders have invested significant effort into removing larger boulders. Further down the ring plain these subsurface debris-avalanche flows have been fluvially reworked, loosening the material and making it more free-draining.

On the southeastern ring plain, the Waingongoro and Inaha catchments have very consistent soils: well-drained, deep tephra deposits with light clay loam to silt loam textures. This tephra cover remains consistent down into the river valleys, only shifting to fluvially reworked sands or flood deposits on the lowest terraces. Along the eastern ring plain boundary deep peats have formed in the basins of blocked-off, west-facing catchments.

On the southwestern ring plain, debris-avalanche flows have formed broad plains with only thin tephra cover, and further west have formed a distinctive mounded landscape with very complex terrain. Soils on the plains are stony and sometimes shallow over welded laharic materials. Among the mounds the soils are highly variable over short distances, comprising a mix of deep loamy ash, buried swamps, and fluvially reworked debris-avalanche flow materials. Weakly cemented iron pans are common in wet areas. Soils along the major rivers are often very sandy, with highly variable depth to gravel deposits.

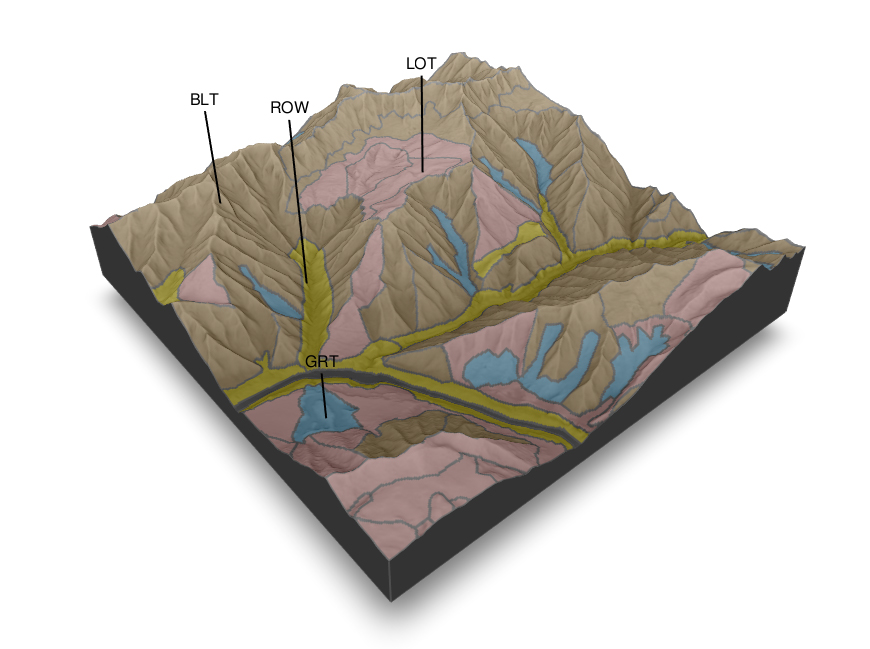

The Waitara catchment is dominated by steep hills with extensive forest cover. The uplifted marine sediments underlying the hills are vulnerable to erosion, even under native cover, and when cleared quickly lose their ash layers on steeper slopes and develop distinctive concave side valleys (Figure 2). Some of the tributary streams have infilled flats, created after massive landslips temporarily blocked stream erosion, but most valleys have only narrow floors or are downcut into gorges. In the lower catchment the terrain softens to rolling hills covered in deep loamy to silty tephra, and a system of low, sandy terraces appears below the Manganui River confluence.

Figure 2. A block diagram showing the soils pattern of an area around the upper Waitara River, looking southeast over the hills. The block is 1 × 1 km. Most of the steep slopes are mapped dominantly as BLT (Typic Allophanic Brown), where thin volcanic ash overlies or is mixed in with materials weathering from the underlying sediments. On lower slopes where mass movement and erosion have less impact, more volcanic ash has accumulated and LOT (Typic Orthic Allophanic) soils predominate. In the lower valley bottoms, ROW (Weathered Orthic Recent) soils can be found where downcutting is active, and GRT (Typic Recent Gleys) soils can be found in the wetter valleys and on low areas on fluvial terraces.

The soils of the National Park remain somewhat mysterious due to lack of physical access. However, enough secondary data has allowed preliminary mapping units to be divided into alpine, subalpine, and lower-slope-forested areas.

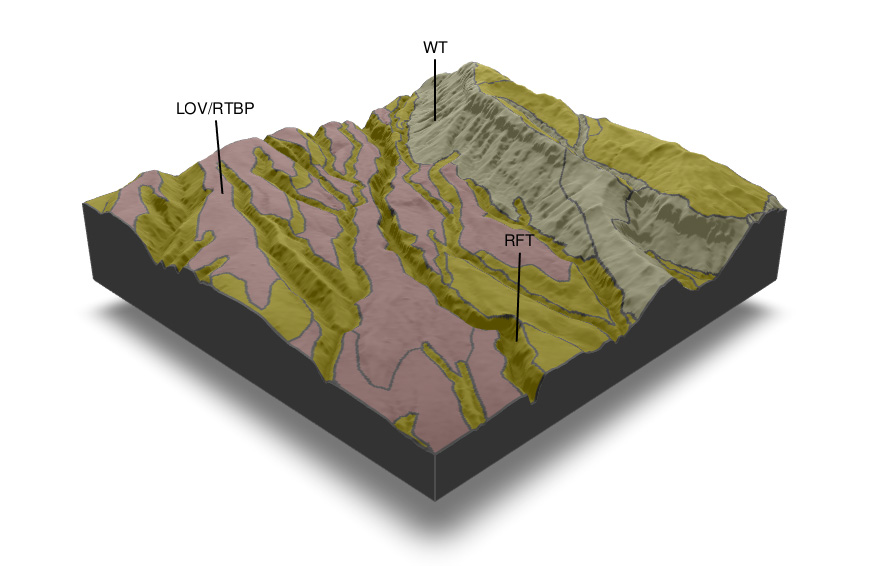

Figure 3. A block diagram showing the soil pattern of an area around the Upper Waingongoro River within Te Papa-Kura-o-Taranaki, looking upstream to the northwest. The Waingongoro Hut is roughly in the middle of the 1 × 1 km block. The dissected stream channels are dominated by RFT (Typic Fluvial Recent) soils formed in materials eroded from the cone, while the gently sloping interfluves are topped with thickly or thinly layered tephras (LOV, Vitric Orthic Allophanic, and RTBP, Buried-pumice Recent Tephric soils, respectively), which are sandy and gravelly due to their close proximity to the main vent. On the steep side slopes where erosion pressure is strong, WT (Raw Tephric) soils are most common.

Soil pattern

Driven by the strong volcanic influence, Taranaki’s soils are largely classified into the Allophanic order in the New Zealand Soil Classification. However, many more areas of Allophanic Browns have been observed than were previously mapped – in the Waitara Hills, where ash cover has eroded away or forms a thin cap over weathered rock, and on the southwestern lahar plains, where cone collapse materials dominate rather than airfall tephra. The new mapping also provides more detail along the major river channels, which are dominated by younger Tephric Gley, Tephric Recent, and Tephric Raw soils. Notably, many areas on the ring plain previously mapped as poorly drained are now regarded as imperfectly drained due to extensive artificial drainage. On the mountain, a progression of stonier, sandier, and younger tephric soils are mapped as the elevation increases, with the summit finally mapped as Rocky Raw soils and bare rock.

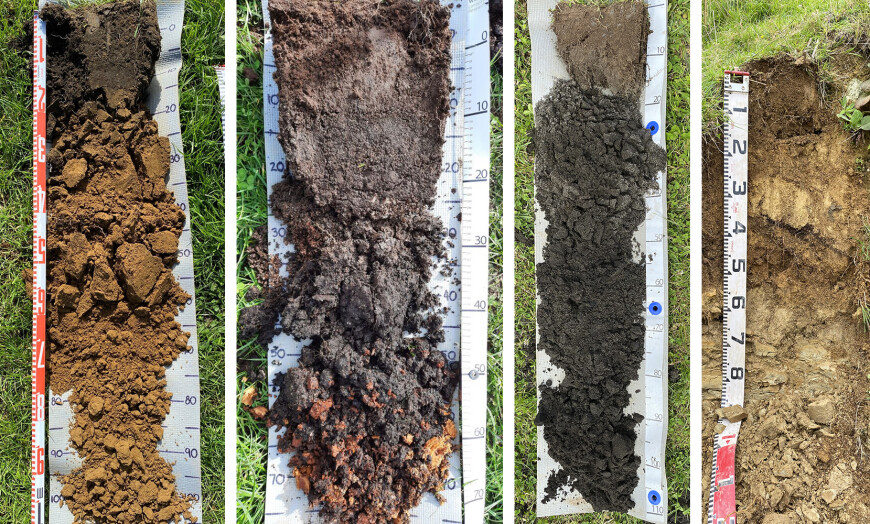

Figure 4. Selected soil profiles. From left to right: deep loamy airfall tephra on a high terrace of the lower Waingongoro River (LOT – Typic Orthic Allophanic Soils); ash-capped fibrous peat on the fringes of Eltham Swamp (OHM – Mellow Humic Organic Soils); deep black sands on low dunes near Pihama (RSK – Tephric Sandy Recent Soils); and thin airfall tephra grading back into weathered siltstone in the middle Waitara catchment hills (LIT – Typic Impeded Allophanic Soils).

References

Landcare Research New Zealand 2000. Fundamental Soils Layer New Zealand.

Palmer RWP, Neall VE, Pollock JA 1981. Soils of Egmont and Part Taranaki Counties, North Island, New Zealand. Lower Hutt, New Zealand Department of Scientific and Industrial Research.