A farmer inspects his sugar beet crop in New Zealand’s vegetable growing hub, Pukekohe

In Aotearoa New Zealand we are feeling this sharply after the COVID-19 pandemic, the war in Ukraine and several extreme weather events that have turned, in the words of Newshub, ‘the fruit bowl of New Zealand into a mud bath’. For the first time since 1987, surging food prices in the country hit a 12.5% high in April 2023.

Manaaki Whenua researcher and senior economist Dr Suzie Greenhalgh and former colleague Dr Tarek Soliman say the recent rising cost of living gives more weight to their 2020 argument that New Zealand should pay more attention to food security at a national level.

In their policy brief, Rethinking New Zealand’s food security in times of disruption, Suzie and Tarek said feeding Kiwis was overlooked in the pressure to produce premium products for the lucrative export market. But the times, they are a changing.

As climate change threatens more extreme weather events globally, staples like sugar, rice, bananas and wheat, and luxuries like coffee could be in short supply.

“People in urban areas generally don’t typically notice the slow changes to food production caused by drought and wet weather disruption, or by the loss of highly productive land to housing developments as we simply import any shortfall,” says Suzie. “However, these are actually the biggest threats to our food security.”

The policy brief proposed several actions that could help the country build resilience into our food systems.

“Addressing consumer issues, such as meeting out-of-season demand and cultural requirements, increasing urban food production, and reducing food waste, are among the first steps we can take as individuals to improve our food security,” says Suzie. “We should also be exploring opportunities for greater domestic production of at-risk commodities.”

She adds that considering how inventive Kiwis can be, with the right support, it shouldn’t be hard to make some of the changes needed. Growing sugar beet could keep us a step ahead of any interruption in sugar supplies that would threaten our baking, brewing and cups of tea.

The food security policy brief formed the foundations for further research to focus on the report’s recommendations. Two key areas the brief says need to be tackled urgently are the issues of food waste and the loss of highly productive land.

“Around 77,000 tonnes of fresh fruit and 74,000 tonnes of fresh vegetables are wasted each year as consumer leftovers,” says Suzie. “Half of all consumer food waste is fresh fruit and vegetables. In 2018 in New Zealand, the waste from potatoes and lettuce alone was estimated at 12,000 and 5,000 tonnes respectively.”

In the first multi-case study research into the return on investment into food rescue in New Zealand, Manaaki Whenua’s Dr Gradon Diprose says the data indicate an investment of $1 in food rescue delivers $4.5 of social value (see below). “This study highlights the transformative potential in addressing food security issues,” he says.

The policy brief’s primary concern was losing New Zealand’s highly productive soils altogether. “Once they are turned into housing, that’s it. They’re gone,” says Suzie.

With just 15% of the country’s land considered highly productive, Manaaki Whenua has worked with Ministry for the Environment, Stats NZ and Waikato Regional Council to develop a new environmental indicator for identifying highly productive land. This tool will help councils identify, map and manage highly productive land under the terms of the 2022 National Policy Statement for Highly Productive Land.

Suzie says land-use decisions need to balance the production of export commodities against local food consumption demands. “It’s not too late and I am confident there are great opportunities to achieve real change in New Zealand to meet our environmental goals as well as meet the nation’s future food demands.”

The value of food waste

Collaborative research between Aotearoa Food Rescue Alliance (funded through the Ministry of Social Development), University of Otago‘s Food Waste Innovation Programme, Manaaki Whenua’s Dr Gradon Diprose (funded by the Resilience to Natures Challenges National Science Challenge) and an independent researcher highlighted the importance of research at the intersection of social concerns (food poverty and access) and environmental concerns (reducing food waste and associated impacts like unnecessary emissions etc). “It’s the first social return on investment for food rescue that considered multiple organisations and different models across supply chains,” says Gradon.

The researchers used the seven guiding principles of social return on investment (SROI) to examine how food rescue generates value for various stakeholders who included food donors, food recipient organisations, food rescue volunteers, and food rescue recipients. Through interviews and analysing quantitative data, the researchers identified nine primary outcomes. Monetary values were assigned to these outcomes, resulting in an SROI ratio of $4.5:1. This indicates a $1 investment in food rescue yields $4.5 worth of social value.

“The research shows we need to evaluate polices that can reduce food waste, find ways to invest in the food rescue sector, and build relationships in the food rescue network,” says Gradon. “By evaluating the outcomes over time in different situations, we can gain more knowledge about the role of food rescue in transforming the overall food system.”

Protecting our highly productive land

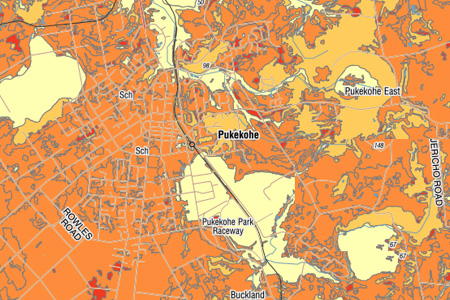

Pukekohe as it appears on S-map, the digital soil map for Aotearoa.

Highly versatile soils are found in various locations across New Zealand, such as Pukekohe for vegetable production, Taranaki and Waikato for dairy, Gisborne for citrus, and Canterbury for seed production.

Recognising the significance of these soils to the country’s export economy, food supply, and employment, the New Zealand Government recently implemented the National Policy Statement for Highly Productive Land (NPS-HPL) that aims to protect the most versatile soils from urban sprawl and rural residential development.

The NPS-HPL recognises highly productive land belonging to Land Use Capability (LUC) classes 1 to 3, which makes up around 14% of New Zealand. Manaaki Whenua, the Ministry for the Environment, Stats NZ, and the Waikato Regional Council developed an environmental indicator to monitor the effects of land fragmentation on highly productive land availability that can be used in conjunction with other existing datasets such as the LUC, S-map, the Land Cover Database and Protected National Areas to support a number of government policies, from infrastructure and land-use planning through to farm management.

All of these datasets highlight the invaluable contribution of nationally significant databases and collections to the intergenerational availability of fundamental knowledge about our natural environment.

Publication

- pdf Policy Brief 27: Rethinking NZ's food security in times of disruption pdf File, 395 KB