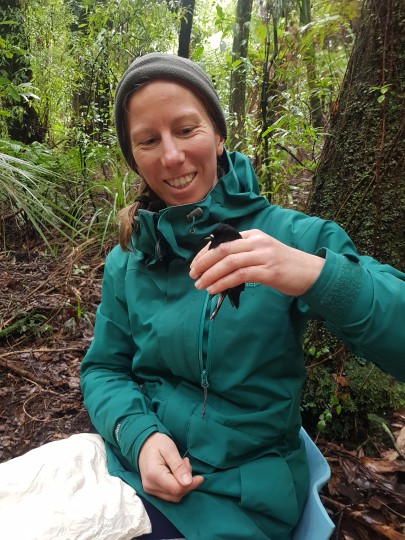

Titipounamu (rifleman)

Worse for the birds, these higher, cooler elevations might be less than optimal places to hang out. Less food may be available for birds, leading to lower survival or breeding success.

Determining the factors that limit populations in this way is fundamental for effective conservation management of New Zealand’s threatened bird species. If places with optimal conditions can be identified, these can be targeted for predator control and lead to faster recovery of dwindling bird populations. However, the relationship between elevation and food supply for forest birds is not well understood at present, and without removing the predators as a limiting factor, secure conclusions about the reasons for bird survival cannot realistically be made.

In new research just published in the New Zealand Journal of Ecology as part of the MBIE Endeavour research programme More Birds in the Bush, Dr Anne Schlesselmann and colleagues at Manaaki Whenua - Landcare Research addressed this knowledge gap, using techniques familiar to many birdwatchers – good binoculars and huge amounts of patience. The work was done at Mt Pirongia, where fortunately predator numbers are routinely suppressed, enabling the effects of elevation on food supply to be more clearly analysed.

In spring and summer 2020/21, working at six sites at each of three different elevations on the sides of Mt Pirongia, the researchers sampled invertebrate prey while simultaneously monitoring the fate of 55 tītitipounamu/rifleman (Acanthisitta chloris) nests and 33 miromiro/tomtit (Petroica macrocephala) nests, and the number of fledglings produced by each. Invertebrates were sampled on the ground and on the wing, and their biomass calculated. Camera traps and tracking tunnels were used to monitor predator numbers.

Anne Schlesselmann with a miromiro (New Zealand tomtit)

Anne says: “This work was incredibly challenging on so many levels. Pirongia has beautiful tall tawa trees and very steep slopes. The only access is through walking up the hill. The higher you are, the windier and colder it is. Following birds in tall canopy was tricky and required a lot of patience as birds are very good at being secretive about their nests.”

Did higher elevation forests provide less food for rat-sensitive, sedentary native insectivorous bird species? If so, were they less successful in breeding at these higher elevations? The results from the 18 sites somewhat supported the theory that there would be less invertebrate food available for the birds at higher elevations, and that their reproductive success would be lower as a result. In general, though, nest survival and number of fledglings produced by tītitipounamu and miromiro was not strongly related to elevation or food availability.

Co-researcher John Innes says: “Studying food availability for birds is harder than studying predation and has been rarely done in New Zealand. Yet we know from overseas research that birds make more nesting attempts when food is abundant. This is the first study that looked for an elevational gradient in reproductive success for New Zealand birds.”

Careful work such as this is the key to understanding likely habitat quality and bird population vulnerability, in order to have thriving bird populations across the motu.