Soil carbon sequestration 101

There is a global need for strategies that actively reduce emissions from fossil fuels, prevent the loss of carbon from soils and vegetation, and remove atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) via sequestration. These strategies need to be feasible to implement, effective, and affordable.

Increasing soil carbon, or preventing losses, is a win-win solution for land managers, by mitigating greenhouse gas emissions while improving soil health. In New Zealand (NZ) the agricultural sector produces about 50% of net anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions.1 The greenhouse gases of most concern are methane, nitrous oxide, and CO2. With approximately 55% of NZ’s land area covered by agriculture,2 farmers play a critical role in maintaining (and potentially increasing) soil carbon to combat climate change.

Carbon sequestration

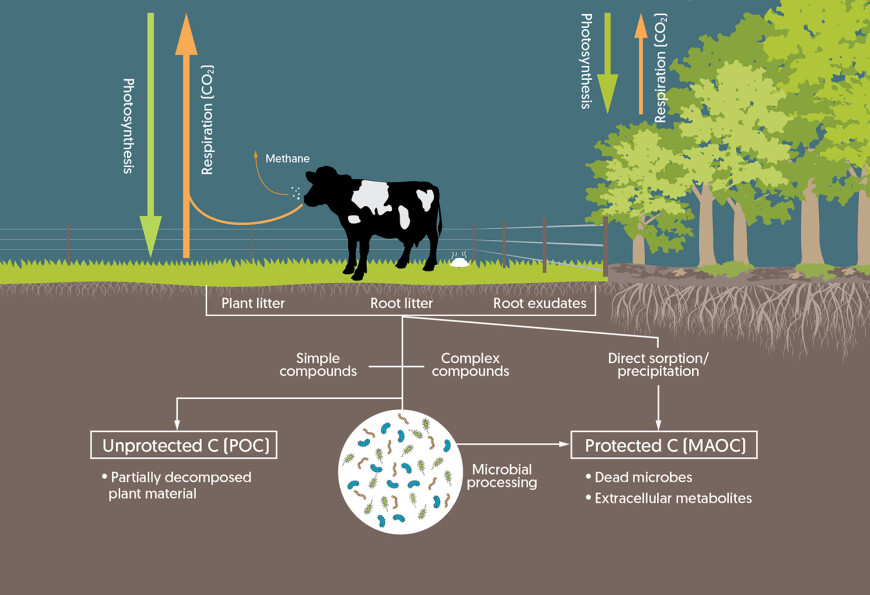

Carbon sequestration is the process by which CO2 from the atmosphere is transferred and accumulates in reservoirs such as soil and plants. Think of carbon as a bank balance, with deposits (e.g. from photosynthesis) and withdrawals (e.g. via respiration) (Figure 1).

A carbon sink absorbs more carbon from the atmosphere than it emits, like a savings account.

A carbon source emits more carbon than it absorbs, like an overdraft.

If we decrease carbon emissions and increase carbon sequestration, eventually we can become ‘debt-free’ (reach net zero).

One area on a farm (for example, a forest) may be a carbon sink, while another (such as a cropping block) may be a source. It is the net balance that matters, and this applies from farm to global scales. From the perspective of climate change, we shouldn’t be concerned about the total stock of carbon in soils or vegetation. It’s the change in these stocks (and whether it’s positive or negative) due to land-use activities that matters most.

Figure 1. Conceptual diagram of the carbon cycle in a farm ecosystem. Carbon dioxide (CO2) is fixed from the atmosphere by plants via photosynthesis. Most of the CO2 fixed is lost from the system via respiration of plants, soil microbes and grazing animals. Some carbon is retained in tree biomass, and some enters the soil as plant litter, root litter, and root exudation, and via dung and urine deposited by grazing animals. Carbon entering the soil is processed through microbial activity and mineral interactions, and a small proportion can be retained in either unprotected particulate organic carbon (POC) or protected mineral-associated organic carbon (MAOC) pools. The thickness of the green and red arrows in the figure is proportional to the carbon flow. To sequester carbon in the system, inputs (green) need to be increased, losses (red) decreased, or both.

Carbon sequestration in soils

Globally, soil contains more carbon than plants and the atmosphere combined. Therefore even modest carbon gains or losses from soil can influence atmospheric CO2 concentrations. Carbon is also important for soil health, improving soil structure, nutrient cycling, water retention, drought resistance, and plant productivity.

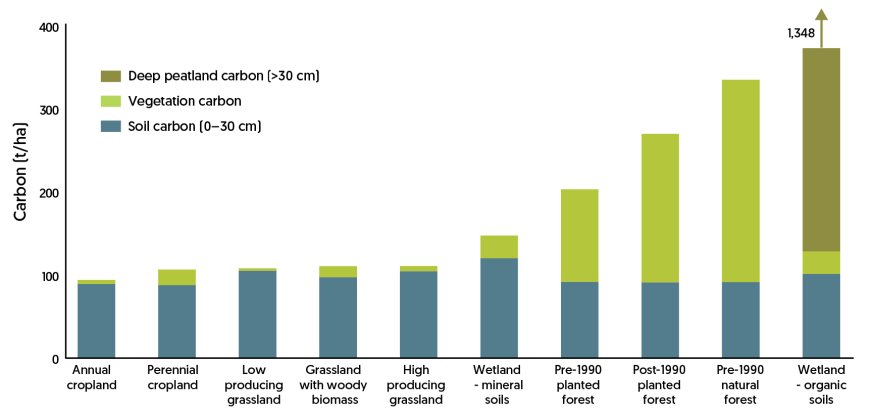

Plants absorb CO2 from the atmosphere for photosynthesis. Much of the absorbed CO2 is released back into the atmosphere via respiration from plants, soil microbes, and grazing animals (Figure 1). A small proportion of total carbon inputs can be retained in the soil, and over time (decades) under a given land use and management regime (e.g. dairy pasture), soil carbon stocks will reach a ‘steady state’, whereby carbon inputs and losses are balanced. Figure 2 shows estimates of steady state soil and vegetation carbon stocks for different land-use classes.

- Types of soil carbon: Soil carbon can be found in two broad forms: particulate organic carbon (POC) and mineral-associated organic carbon (MAOC). MAOC is tightly bound to soil mineral particles, making it ‘protected’ and less accessible to microbes, while POC remains ‘unprotected’ and is more readily decomposed (Figure 1).3 Both forms are beneficial, but MAOC is generally more stable and therefore critical for long-term carbon sequestration.

- The role of soil microbes: Microorganisms are crucial in multiple direct and indirect ways for soil carbon sequestration. Microbes directly contribute to carbon accumulation by breaking down plant inputs into organic matter (a combination of carbon and other elements), releasing some CO2 back into the atmosphere in the process. Microbial activity shapes soil aggregate structure and facilitates the transfer of carbon between unprotected and protected forms. Microbial biomass itself is a key precursor to stabilised soil carbon.4,5

- Importance of Organic Soils: Organic Soils (also known as peat soils) are slowly formed over thousands of years from the accumulation of partially decomposed plant material in areas where high water-tables slow the decomposition process. When land is drained for agriculture, lowered water-tables facilitate oxygen diffusion into the soil, increasing decomposition rates and leading to permanent loss of soil carbon as CO2. Approximately 90% of NZ’s Organic Soils have been drained, and they contribute 6–7% of national net greenhouse gas emissions despite occupying only about 1% of the land area.22

The influence of land use and management on soil carbon

In the previous sections we reviewed the soil carbon cycle and discussed why preventing losses and sequestering soil carbon is important for NZ. In this section we provide an overview of how land use and land management practices can affect soil carbon, and then give a snapshot of current and recent research projects.

The effect of land use

It’s well established that changes from one land use to another can lead to shifts in total carbon stocks. Figure 2 provides estimates of carbon stocks across different broad land-use classes in NZ, separated into soil and vegetation carbon stocks.

Changes in land use often have a more pronounced effect on vegetation carbon, but soil carbon can also change. For instance, converting grassland to forest tends to decrease soil carbon, but total ecosystem carbon increases because more carbon becomes stored in woody biomass. Converting grassland to cropland reduces soil carbon stocks, while the reverse occurs when cropland is converted to grassland (Figure 2).

NZ’s national soil carbon inventory tracks how land-use changes affect soil carbon through time. This reporting assumes a linear change; for example, if grassland is converted to annual cropland over 20 years, soil carbon stocks are predicted to decline from a steady state of about 105 tonnes of carbon per hectare (t/ha) to a new steady state of about 92 t/ha1. We are currently working on a project with the Ministry for the Environment to update the current national soil carbon inventory database and modelling approach for mineral soils. Similar work has recently been undertaken for Organic Soils (peatlands) for the Ministry for Primary Industries7.

Figure 2. Soil and vegetation carbon stocks across various land-use types, measured in tonnes per hectare (adapted from Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment, 20198,9). Soil carbon stocks measured to 30 cm depth are shown, except for wetlands on Organic Soils (peatlands), which include an estimate based on average peatland depth (3.9 m).10 Mineral soils also contain carbon deeper than 30 cm, but there are fewer measurements recorded, so estimates are less certain. Note: estimates of soil carbon stocks for different land uses will be refined and updated periodically as new data are collected and analysed.

The effect of land management practices

While there is good evidence that changes in land use can influence soil carbon stocks in NZ (see Figure 2), there is less information on the effects of management practices within a land use, and results are not as clear or consistent. Further research is required.

A few NZ studies have shown no effect of long-term superphosphate fertiliser application on soil carbon stocks in pastoral systems11, and within a cropping system, tillage method had no effect on carbon stocks12. One study revealed lower soil carbon stocks in the topsoil of dairy compared to adjacent drystock farms13. Four studies14,15,16,17 have reported less carbon under irrigated than adjacent dryland pastures, but another study of net carbon balances found no clear effect of irrigation18. Periodic cropping for supplemental feed in pasture systems has been shown to result in large losses of soil carbon in the short term,18,19 and further research is needed to determine the longer-term implications.

A synthesis of carbon balance measurements from Waikato and Canterbury dairy farms found that conventional rye–clover pasture swards were better for soil carbon stocks than more diverse swards (though the latter may offer other benefits)18. Planting tree clusters, shelterbelts, and riparian zones can increase net carbon sequestration on the farm20 while also improving soil health, water quality, erosion control, biodiversity, and providing livestock shelter. Ongoing research is investigating the impact of tree patches on soil carbon, specifically (see below).

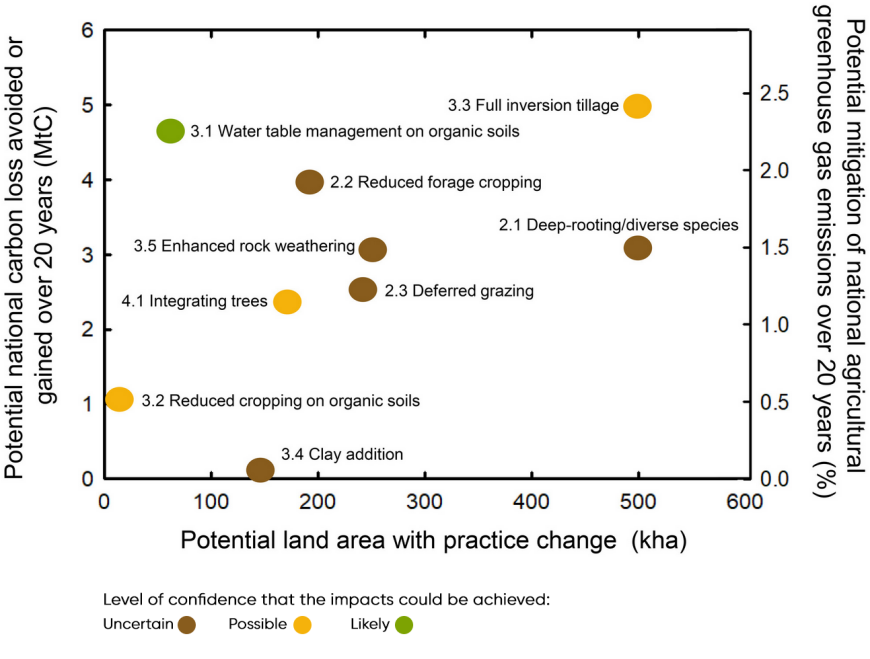

A recent study by Whitehead et al.21 evaluated nine management interventions that could be implemented in NZ to reduce soil carbon losses or increase stocks. Figure 3 provides a graphical summary of the results. They concluded that, currently, ‘water table management, which reduces carbon loss from organic soils, was the only intervention that could achieve moderate, short- and long-term impacts with a confidence level assessed as "likely" 21. International research has shown that raising the water-table in Organic Soils used for agriculture can substantially reduce (but not stop) CO2 emissions. Research in NZ is now beginning to investigate whether this is also true for our unique peatlands, the practicalities of raising water-tables, and alternative productive land uses for farming on higher water-tables.

Figure 3. Figure from Whitehead et al.21 showing the potential impacts of nine management interventions to avoid losses or increase soil carbon stocks at the national scale over a period of 20 years in relation to the potential land area where adoption could be achieved. On the right-hand axis the impacts are shown as a percentage of national agricultural greenhouse gas emissions over 20 years. The colours of the filled circles for each intervention show the level of confidence the impacts could be achieved.

A snapshot of soil carbon research projects

National Soil Carbon Benchmarking and Monitoring Programme

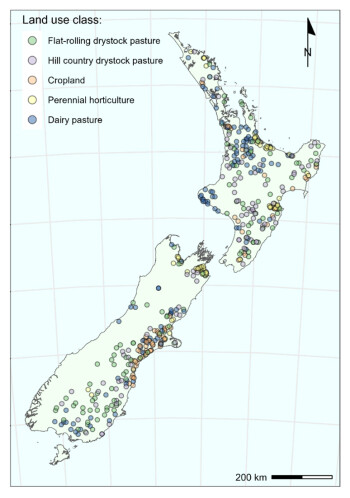

Figure 4. Distribution of soil carbon sampling sites across New Zealand from Mudge et al. 2025: Design and results from a national soil carbon stock benchmarking and monitoring system for agricultural land in New Zealand CC BY 4.0.

This project monitors changes in soil carbon stocks through time and over different regions, land uses, and soil types at 500 sites. There are approximately 100 sites in each of the following land-use classes (ordered by highest to lowest soil carbon):

- dairy pasture

- hill-country drystock pasture

- flat-rolling drystock pasture

- perennial horticulture

- cropland.

The benchmark sampling took place from 2018 to 2024, and sites will be resampled three times by 2032. Preliminary results have shown that average soil carbon stocks across all of the five land categories were higher than in most other countries thanks to NZ’s favourable climate and perennial vegetation. More details on the study design and benchmark results can be found in a peer-reviewed publication here or a summary article here.

Improving the National Soil Carbon Inventory

The NZ greenhouse gas inventory is required for international reporting and helps us calculate farm and industry emissions. Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research, a group of the Bioeconomy Science Institute, is working with the Ministry for the Environment to improve the data and modelling of the national carbon inventory for mineral soils to address some of the uncertainty relating to key assumptions and under-represented land uses.

Modelling and measuring agricultural management on peat soils

Peatland drainage has led to an outsized contribution to NZ’s net greenhouse gas emissions. This international research programme, a collaboration between researchers from NZ and Ireland, seeks to improve data on peatlands, including farming on shallow drainage, reflooding peat soils, rates of land subsidence, and general strategies for lowering carbon emissions without significantly affecting farm productivity. A recorded webinar provides a broad overview of research in NZ on Mitigating Greenhouse Gas emissions from drained peat (Organic Soils).

Trees in landscapes

Patches of trees less than 1 hectare in area integrated in the farm landscape are currently excluded from the Emissions Trading Scheme despite their contribution to carbon storage (as well as many other co-benefits). This programme is investigating how tree groups affect soil carbon over different soil types and regions, and with different tree species.

Farm- and paddock-scale measurements

Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research and the University of Waikato have partnered to study the effects of management practices on paddock-scale emissions. Early findings emphasise the importance of minimising fallow periods. Researchers have also developed a farm-scale carbon monitoring protocol using direct soil measurements, which is now being adopted by some farmers. International protocols are also available, such as from the FAO and the Australian Government.

References

1Ministry for the Environment 2024. New Zealand’s Greenhouse Gas Inventory 1990–2022. Wellington, Ministry for the Environment. https://environment.govt.nz/assets/publications/GhG-Inventory/2024-GHG-inventory-2024/GHG-Inventory-2024-Vol-1.pdf

2Whitehead D, Schipper LA, Pronger J, Moinet GYK, Mudge PL, Calvelo Pereira R, et al.2018. Management practices to reduce losses or increase soil carbon stocks in temperate grazed grasslands: New Zealand as a case study. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 265: 432–443. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2018.06.022

3Lavallee JM, Soong JL, Cotrufo MF 2020. Conceptualizing soil organic matter into particulate and mineral‐associated forms to address global change in the 21st century. Global Change Biology 26: 261–273. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.14859

4Cotrufo MF, Wallenstein MD, Boot CM, Denef K, Paul E 2013. The Microbial Efficiency-Matrix Stabilization (MEMS) framework integrates plant litter decomposition with soil organic matter stabilization: do labile plant inputs form stable soil organic matter? Global Change Biology 19(4): 988–995. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12113

5Gougoulias C, Clark JM, Shaw LJ 2014. The role of soil microbes in the global carbon cycle: tracking the below‐ground microbial processing of plant‐derived carbon for manipulating carbon dynamics in agricultural systems. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 94: 2362–2371. https://doi.org/10.1002/jsfa.6577

6Pronger J, Glover-Clark G, Campbell D, Price R, Schipper L 2022. Improving accounting of emissions from drained organic soils. MPI Technical Paper No. 2023/16. Wellington, Ministry for Primary Industries.

7Pronger J, Price R, Glover-Clark G, Fraser S, Goodrich JP, Campbell D, et al. 2025. Improving Organic Soil activity data. Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research contract report LC4625, prepared for the Ministry for Primary Industries.

8Ministry for the Environment 2019. New Zealand’s Greenhouse Gas Inventory 1990–2017. Wellington, Ministry for the Environment.

9Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment 2019. Farms, forests and fossil fuels: the next great landscape transformation? Wellington, Parliamentary Commissioner for the Environment.

10Ausseil A-GE, Jamali H, Clarkson BR, Golubiewski NE 2015. Soil carbon stocks in wetlands of New Zealand and impact of land conversion since European settlement. Wetlands Ecology and Management 23: 947–961. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11273-015-9432-4

11Schipper LA, Mudge PL, Kirschbaum MUF, Hedley CB, Golubiewski NE, Smaill SJ, et al. 2017. A review of soil carbon change in New Zealand’s grazed grasslands. New Zealand Journal of Agricultural Research 60(2): 93–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/00288233.2017.1284134

12Curtin D, Beare MH, Qiu W 2021. Distinguishing functional pools of soil organic matter based on solubility in hot water. Soil Research 59(4): 319–328.

13Barnett AL, Schipper LA, Taylor A, Balks MR, Mudge PL 2014. Soil C and N contents in a paired survey of dairy and dry stock pastures in New Zealand. Agriculture Ecosystems & Environment 185: 34–40.

14Schipper LA, Dodd MB, Pronger J, Mudge PL, Upsdell M, Moss RA 2013. Decadal changes in soil carbon and nitrogen under a range of irrigation and phosphorus fertilizer treatments. Soil Science Society of America Journal 77(1): 246-256.

15Condron LM, Hopkins DW, Gregorich EG, Black A, Wakelin SA 2014. Long-term irrigation effects on soil organic matter under temperate grazed pasture. European Journal of Soil Science 65(5): 741–750.

16Mudge PL, Kelliher FM, Knight TL, O'Connell D, Fraser S, Schipper LA 2017. Irrigating grazed pasture decreases soil carbon and nitrogen stocks. Global Change Biology 23(2): 945–954. https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.13448

17Mudge PL, Millar J, Pronger J, Roulston A, Penny V, Fraser S, et al. 2021. Impacts of irrigation on soil C and N stocks in grazed grasslands depends on aridity and irrigation duration. Geoderma 399: 115109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2021.115109

18Wall AM, Laubach J, Campbell DI, Goodrich JP, Graham SL, Hunt JE, et al. 2024. Effects of dairy farming management practices on carbon balances in New Zealand’s grazed grasslands: synthesis from 68 site-years. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 367: 108962. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.agee.2024.108962

19Wall AM, Campbell DI, Morcom CP, Mudge PL, Schipper LA 2020. Quantifying carbon losses from periodic maize silage cropping of permanent temperate pastures. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 301: 107048.

20Richards D, Allen K, Graham S, Harcourt N, Kirk N, Lavorel S, et al. 2024. Carbon stocks and sequestration from small tree patches in grassland landscapes in Aotearoa-New Zealand. Climate Policy 25(7): 977–995. https://doi.org/10.1080/14693062.2024.2427710

21Whitehead D, McNally SR, Graham SL, Pronger J, Wall AM, Isson T, et al. 2024. Evaluation of the potential for nine established and emerging interventions to reduce soil carbon losses and increase stocks in grazing systems: a case study for Aotearoa New Zealand. Soil Use and Management 40(3): e13113.

22 Goodrich, JP, Pronger J, Campbell DI., Glover-Clark GL., Price R, Mudge PL, Wyatt J, Robertson H, Wall AM, Wheatley-Wilson A, Schipper LA 2025. Large Greenhouse Gas Emissions From Drained Peatlands in New Zealand, and the Climate Mitigation Potential of Rewetting. Mires and Peat 32, 29. https://doi.org/10.19189/001c.147886