It’s time to take on purple loosestrife

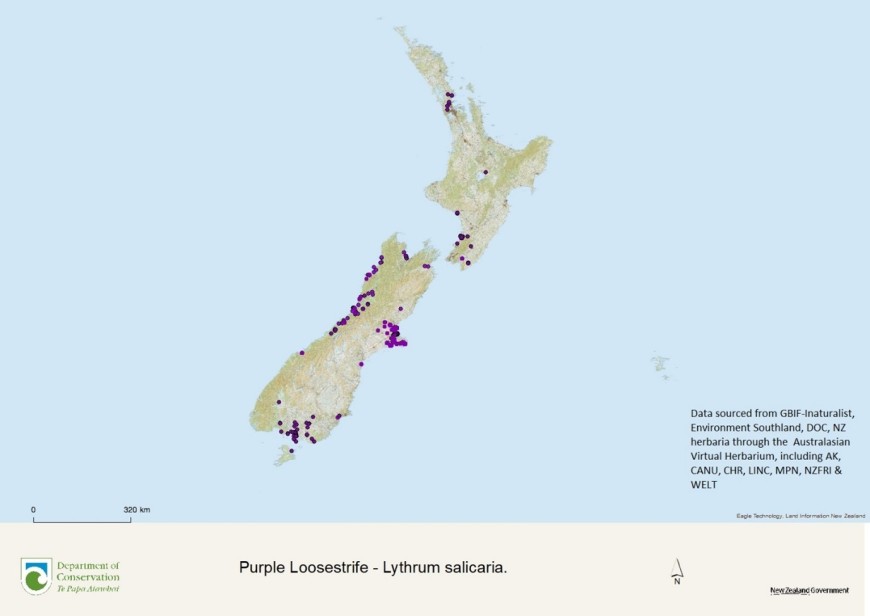

Then in 2021, Horizons Regional Council (HRC) approached us to undertake a feasibility study and surveys of the weed in New Zealand to assess the potential for developing a successful biocontrol programme for purple loosestrife. The worst infestations occur in Horowhenua in the Manawatū-Whanganui region on the west coast of the North Island. Fully naturalised populations occur in Canterbury, and scattered and isolated populations occur in Auckland, Taranaki, Bay of Plenty, the Wellington Region, Southland, the West Coast and Marlborough.

“Eradication of purple loosestrife in Manawatū-Whanganui (Lakes Horowhenua and Papaitonga, Hokio stream and Lake Virginia) was originally part of HRC’s pest management plan, when infestations were estimated to cover less than 30 ha. But the purple loosestrife population in Lake Horowhenua – the largest in the country – became difficult to manage due to accessibility issues and limited herbicide tools available for use in wetlands,” explained Craig Davey, Biodiversity, Biosecurity & Partnerships Manager at HRC. “The expanding populations of purple loosestrife on the margins of Lake Horowhenua are also putting pressure on nearby lakes, with new sites being discovered and previously well-managed infestations at a higher risk of re-invasion,” he added.

Purple loosestrife originates from throughout Europe and Asia, except for the high mountainous regions and most northerly latitudes, and from south-eastern Australia and Tasmania. It was introduced here as a garden ornamental and was first recorded as naturalised in 1958. It is an erect, herbaceous, perennial herb with tall shoots (20–300 cm) and large, spiked inflorescences with clusters of showy, purple flowers. It was particularly popular as a residential pond plant and for stream plantings, and from there it escaped to invade aquatic and semi-aquatic habitats, roadside ditches, and even pastures on farmland. Seeds are mainly spread via waterways, but also by birds, livestock, contaminated machinery, hay and footwear. The illegal sharing of garden cuttings may also be an issue.

Purple loosestrife infestation

Clonal colonies of purple loosestrife develop from woody rootstocks, which produce new shoots each spring. Seedlings are highly competitive, and can develop an extensive rootstock and reach a height of over 1 metre in their first year of growth. The weed rapidly invades damp ground and shallow water, such as wetlands, lake margins, and streams and rivers, forming dense monocultures and excluding native vegetation. Purple loosestrife has the potential to displace all other wetland and riparian flora, drastically altering native ecosystems and reducing food sources for many species of fish and birds. The recreational and aesthetic values of wetlands, lakes, rivers and streams are reduced by dense infestations of purple loosestrife. They block a view of and access to the water and reduce native biodiversity. On farmlands, debris from purple loosestrife stands clogs irrigation pumps and drainage canals.

Current distribution of purple loosestrife

In 2021 a lake restoration project was initiated to restore the water quality and native biodiversity of Lake Horowhenua, which is one of New Zealand’s most polluted lakes. Effective management of purple loosestrife and other invasive weeds is vital to restoring the lake’s social, cultural, environmental and economic values. Biocontrol of purple loosestrife (and other weeds such as yellow flag iris [Iris pseudacorus]) was seen as potentially the most viable option for suppressing populations around the lake and to contain its spread to other, uninfested regions. Control with the use of chemicals is not only undesirable in wetland and other aquatic habitats, but also a deeply objectionable control method with local communities. It is also not economically viable in the long term.

In the United States of America (US) and Canada, where purple loosestrife is a widespread and damaging invasive weed, conventional control methods consistently failed to provide an acceptable level of control of the weed to mitigate its negative economic and environmental impacts. Often, wetlands with extensive purple loosestrife seedbanks ended up with worse infestations following herbicide applications due to rapid seedling recruitment and the loss of native species. A classical biocontrol programme was initiated in 1986 with the aim of reducing the demand for herbicide use in sensitive native habitats and to facilitate the recovery of native biodiversity.

Four biocontrol agents have been introduced into the US for the biocontrol of purple loosestrife, three of which were released in 1992: two leaf-feeding chrysomelid beetles (Galerucella pusilla and G. calmariensis) and a root-feeding weevil (Hylobius transversovittatus). The fourth agent, a flower-feeding weevil (Nanophyes marmoratus), was released in 1994. The weed biocontrol programme against purple loosestrife has been one of the most widely implemented programmes there. In several states, infestations of the weed were reduced by up to 90% in the first 10 years of the programme. Evidence of reduced pesticide use was indicated by a reduction in herbicide purchases. Local eradication has even been achieved at some sites, while dramatic declines in the abundance of purple loosestrife, with reduced shoot densities, were achieved at others.

“With the knowledge of a successful biocontrol programme in the US, we conducted a feasibility study for HRC to assess the prospects of developing a successful biocontrol programme for this weed in New Zealand, and to estimate the costs”, explained Angela Bownes who is leading the project. “The study concluded that biocontrol is a highly viable option for managing purple loosestrife in New Zealand, and that all four biocontrol agents established in North America pose no risk to any native or taonga plant species,” she added. Based on evidence from the field in the US, some minor, non-target feeding damage by the leaf beetles to the exotic ornamental crepe myrtle (Lagerstroemia indica) is likely, and feeding damage to cultivars of two other exotic ornamentals (Lythrum virgatum and L. limii) is possible. Some minor spill-over attack on exotic wild roses may also occur if growing in close proximity to purple loosestrife.

The next step of the project is to prepare a release application to the Environmental Protection Authority. Consultation with iwi and hapū in the Horowhenua region has already begun to assess the cultural impacts, and this will be expanded to other regions of the country where purple loosestrife has established. All going well, we hope to import the leaf beetles and the root weevil into New Zealand in 2023.

This project is funded by Horizons Regional Council.

Contact