Fake clues: using misinformation about odour to protect rare bird species

Dr Grant Norbury preparing a camera trap, Tekapo

As part of long-running research into the behaviour of introduced mammalian predators in New Zealand and Australia, researchers from MWLR and the University of Sydney asked whether it might be possible to manipulate predator behaviour by using misinformation. Could we use unrewarded prey odour cues to fool predators and make them ignore real prey cues? If we could make predators less efficient at hunting, might we also make them miss real prey?

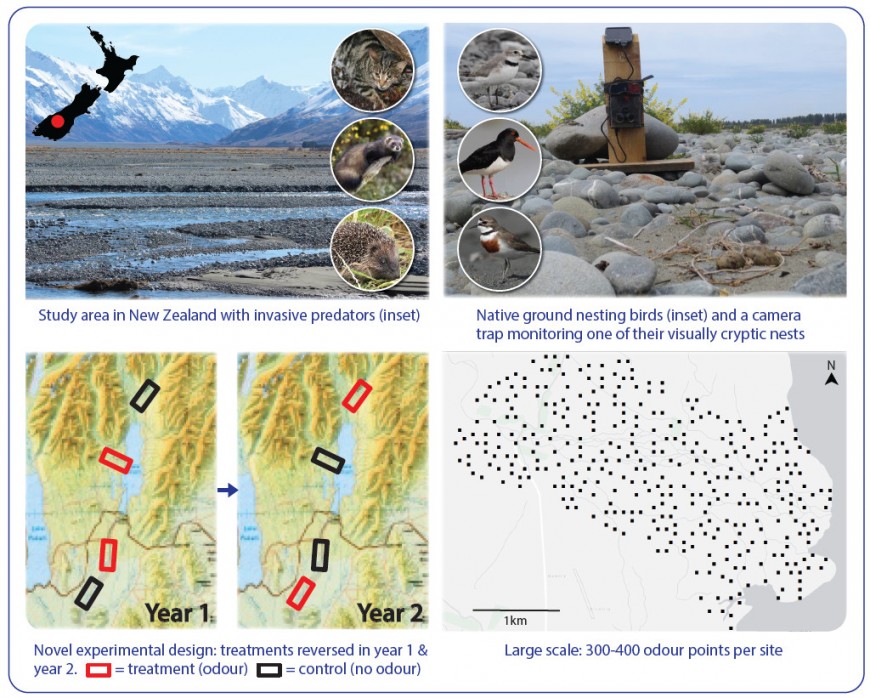

Over two nesting seasons the researchers tested the response of cats, ferrets, and hedgehogs to false odour cues at nesting sites for three shorebird species – banded dotterel (tūturiwhatu), wrybill (ngutu-parore) and SI pied oystercatcher (tōrea). These native bird species nest on the ground on braided rivers in Canterbury and are highly vulnerable to predators.

The researchers made odorous pastes from the carcasses and feathers of readily available birds – such as chickens, quails, and black-backed gulls – and tested whether repeated exposure to these odours would affect the predators’ behaviours. They set out the pastes at 300 to 400 points across nesting sites every 3 days for 5 weeks before the birds arrived to nest, and for 8 weeks thereafter during the nesting season. Predators’ behaviour was then compared to that at sites without paste. Camera traps were used to monitor predators’ interest in the paste, and to monitor the survival of nests at sites with and without odour paste. In the second nesting season the paste/no-paste sites were swapped to increase the reliability of the results.

Photos show (top to bottom left) camera trap images of ferret, hedgehog and cat encountering odour pastes; (top to bottom right) the same species preying on bird eggs.

All three types of predator were attracted by the paste odours, but ferrets and cats, in particular, quickly lost interest after 12–18 days when there were no prey associated with the scent cues. By the time nesting started, interactions with odour were only 5–9% of their initial values. Hedgehogs began emerging from hibernation shortly after the study began so their interest in the odour initially increased, given they were very hungry, but their interest quickly declined thereafter. As a result, when the birds arrived to nest, the predators had already habituated to unrewarded bird odour cues and ignored bird odour, including that of the real birds.

The effects on nest survival were striking for all three bird species: compared with non-treated sites, odour treatments resulted in a 1.7-fold increase in chick production over 25–35 days and doubled or tripled the odds of successful hatching. Protecting nests laid in the first third of the nesting season provided a disproportionately greater benefit because their survival is naturally higher than for nests laid later. For banded dotterels, the researchers modelled the effects on population growth and estimated that this intervention could result in a 127% increase in population size in 25 years of annual odour treatment, compared with population declines with no treatment.

The study area showing the study species (predators, top left, and native ground-nesting birds, top right), the experimental design with treatments reversed at each of the four sites each year (bottom left), and the scale of the deployment of the 300–400 odour points at each site (bottom right). (Photo credits – background images: Grant Norbury, Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research)

The method would never replace lethal control and is a niche approach best suited to small areas of vulnerable biodiversity where lethal control methods are difficult to implement, or where the social licence to use lethal methods is absent. The method also opens significant opportunities in other countries where lethal control of native predators is not an option.

Lead researcher Dr Grant Norbury of MWLR worked with colleagues at the University of Sydney, Dr Catherine Price and Prof Peter Banks, who developed the idea. Dr Norbury says that this field experiment shows that altering perceptions of prey availability offers a novel, non-lethal approach to managing problem predators, and ‘could significantly reduce predation rates and produce population-level benefits for vulnerable prey species at ecologically relevant scales, without any direct interference with animals.’