Senior researcher and geospatial modeller Dr Alexander Herzig says the characteristics of landscapes, and the location and intensity of human activities within those landscapes all play a role in the country’s ability to grow food, provide fresh water, regulate climate, and control erosion.

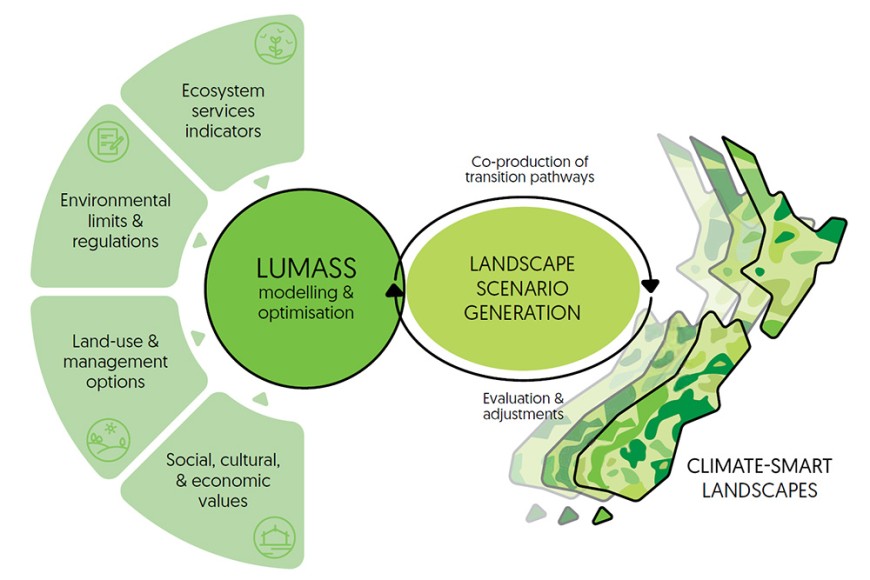

This landscape knowledge, represented by spatially explicit data on, for instance, climate, soils, and crop performance, can be processed with the Land-Use Management Support System (LUMASS) to help stakeholders develop pathways or management plans for more climate-resilient landscapes.

Illustrating the use of LUMASS for land-use scenario generation.

Alex and his collaborators, led by Professor Rich McDowell (Our Land and Water), were able to demonstrate the use of LUMASS in a recently published joint study of the Our Land and Water and Healthier Lives National Science Challenges in the Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand.

The study, Growing for good: producing a healthy, low greenhouse gas and water quality footprint diet in Aotearoa New Zealand, tested different land-use scenarios to see whether New Zealand could profitably produce enough crops, in the right places, to feed all New Zealanders a healthy diet, and still meet its ambitions to lower greenhouse gas emissions and nutrient losses to water.

For the study, researchers ran tests under two different scenarios. The first scenario, a climate-focused one, aimed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by removing up to 13% of stock (as outlined by the Climate Change Commission). It replaced dairy land with crops, and sheep and beef systems with forestry. The second freshwater-focused scenario allowed crops and forestry to expand onto all pastoral farming systems until nitrogen and phosphorus losses were low enough to reduce algal growth in rivers, lakes or estuaries.

“In both cases, we targeted areas that currently don’t meet environmental standards for nitrogen and phosphorus pollution and that would likely benefit from land-use change,” says Alex. “However, we also had to expand into other areas to meet the crop growth targets required by a healthy diet.”

Alex says the cost of making these changes to land use was about 1% of the revenue generated by New Zealand’s primary sector exports, which is a relatively small amount. “In fact, it was much lower than the estimated savings that could be achieved in the healthcare system by optimising people’s diets,” he says.

“Being smart about where and how we use the land for food production helps with meeting our environmental goals related to greenhouse gases, nitrogen, and phosphorus pollution, as well as saving money and improving the health of the people in New Zealand,” he says.