That’s the premise behind new research into silvopastoral system design – or what happens when you combine “space-planted” trees (trees planted at low density) with the production of livestock.

“At the moment there is a very one-dimensional approach to planting trees,” says Dr Thomas Mackay-Smith, a Massey University researcher.

“Poplar and willow are easily planted, survive grazing livestock and perform well in terms of soil erosion, but there could be other tree species out there that provide additional value to farmers. The challenge is selecting the right tree species to provide a holistic suite of benefits.

“In New Zealand, there has been little formalised research comparing the impact of different tree characteristics – or ’functional traits‘ – on farm outcomes, or the processes that govern these interactions.”

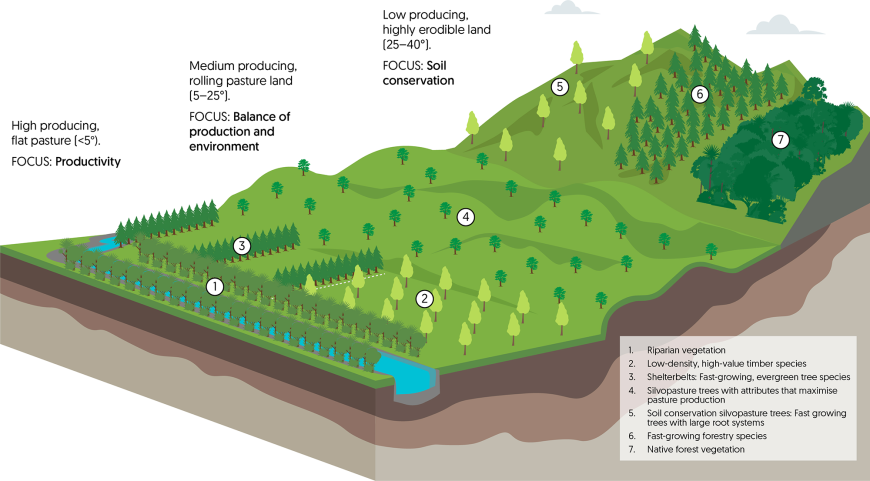

Silvopasture – a graphic representation of an ideal landscape.

Manaaki Whenua’s Raphael Spiekermann agrees. He says while traditionally trees have been removed from the landscape to allow farming to happen, and are now planted for soil conservation, it is challenging to predict the outcomes of planting new trees due to the complexity of the relationships within a silvopastoral system.

“We undertook a review of ecological research from around the world to find evidence for the influence of key tree attributes and processes on silvopastoral outcomes.”

The evidence showed livestock can have overriding influences on the silvopastoral environment, and livestock activity needs to be an essential consideration when comparing outcomes between systems. “More work is required to measure livestock preferences for different tree species, in what situations livestock preferences exist, and how the impact of livestock activity as a process compares to direct tree processes like litter decomposition or competition for water,” says Thomas.

“More research is also needed to explore the impact of a broader range of tree functional traits and silvopasture processes on farm outcomes, such as tree size, tree architecture, tree water use efficiency, livestock preferences for different tree species, leaf smother and inhibition of other plant species (allelopathy). This information will allow us to better design silvopastoral systems using an integrative and holistic approach to maximise their positive impacts for farms.”

Participants at a workshop held as part of the silvopastoral system design research.

The researchers held a successful workshop with around 35 farmers as part of the study. Poplar (Populus spp.), followed by willow (Salix spp.) and eucalyptus (Eucalyptus spp.) trees, were the most common silvopastoral trees planted, but other species were also planted such as tagasaste (Cytisus proliferus), cork oak (Quercus suber), acacia (Acacia spp.), chestnut (Castanea spp.), Tasmanian blackwood (Acacia melanoxylon), maple (Acer spp.), radiata pine (Pinus radiata), ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba) and mānuka (Leptospermum scoparium).

“We found landowners already had considerable knowledge of the future potential of silvopastoral systems,” says Raphael. “But there are barriers to the future adoption of these systems.”

These barriers include the regulatory environment for New Zealand’s Emissions Trading Scheme, timescale issues such as the time lag until the trees become effective, difficulties protecting seedlings, and the costs involved with planting and management.

“There is great promise for silvopastoral trees to provide a range of benefits to farms,” says Thomas. “While many farmers are already planting trees in their paddocks, it is important future research covers a broader range of tree species to increase our knowledge as to which trees will be important for different functions on the farm.”

Funding

This research was funded by the Our Land & Water National Science Challenge.

Key contact