Regenerative Agriculture White Paper Sets Out Pressing Research Priorities

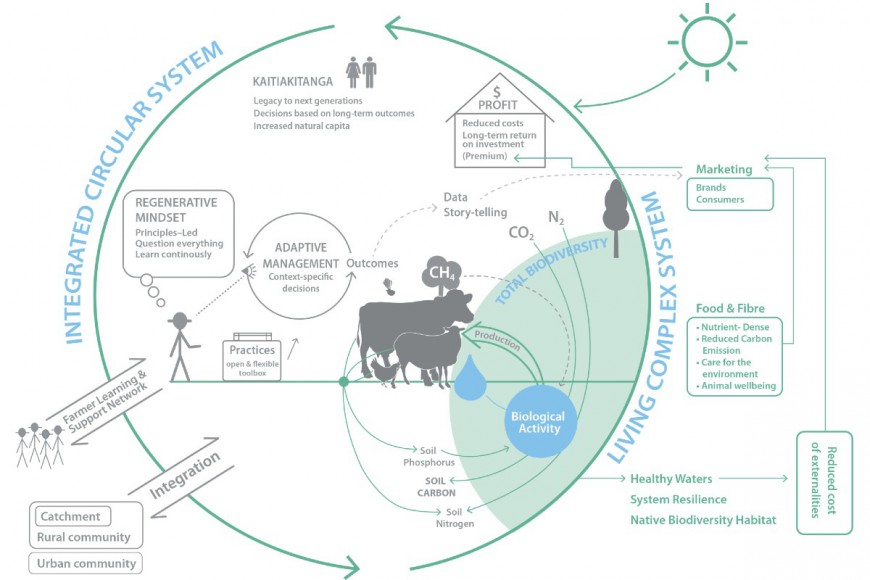

Regenerative agriculture lifecycle

Regenerative agriculture has been proposed as a solution for some of Aotearoa New Zealand’s most acute challenges. Advocates suggest it can improve the health of our waterways, reduce topsoil loss, offer resilience to drought, add value to our primary exports, and improve the pervasive well-being crisis among rural farming communities.

With a groundswell of farmers transitioning to regenerative agriculture in New Zealand, there is an urgent need for clarity about what regenerative agriculture is in New Zealand and for scientific testing of its claimed benefits.

A new white paper, Regenerative Agriculture in Aotearoa New Zealand – Research Pathways to Build Science-Based Evidence and National Narratives, sets out 17 priority research topics and introduces 11 principles for regenerative farming in New Zealand.

Lead author Dr Gwen Grelet, senior researcher at Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research, says that although evidence is urgently required, regenerative agriculture potentially has an important role to play in New Zealand.

“Regenerative agriculture has huge momentum internationally in all parts of the food system. It is not a magic bullet but its grass-roots popularity with farmers and food consumers mean it has huge potential for driving the transformation of Aotearoa’s agri-food system to move our country closer to its goals.

“Our consultation found many areas of strong agreement between advocates and sceptics. It’s time to stop bickering and focus on identifying any true benefits regenerative agriculture might have for New Zealand.”

The white paper is the result of intensive collaboration and consultation with more than 200 people from June to November 2020. Collaborators include farmers and growers, researchers, primary industry bodies, banks, retailers, non-governmental organisations, government departments, large corporates, consultants, marketers, overseas researchers and educators.

The project was funded by the Our Land and Water National Science Challenge, the NEXT Foundation and Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research.

What is ‘regen ag’ and what does it mean for New Zealand?

While a succinct definition of regenerative agriculture would be useful for marketing purposes, the white paper refrains from offering a definition for two reasons: the risk of constraining an evolving concept, and the need for any New Zealand definition to be anchored in te ao Māori (the Māori world view). Collective work by Māori experts and practitioners is currently in progress to identify linkages between te ao Māori cultural concepts and regenerative agriculture principles.

“Our research examined people’s understanding of regenerative agriculture through outcomes, principles, practices and mindset,” says research co-lead Sam Lang, farmer and manager of the Quorum Sense farmer extension project. “We found that all are important. While it is tempting to focus on novel or innovative practices, exploring the influence of farming principles and farmers’ mindsets could be more valuable.”

The white paper identifies 11 principles for regenerative farming within the farmgate in New Zealand, with strong alignment between the pastoral, arable and viticulture sectors.

The 11 principles are: (1) The farm is a living system, (2) Make context-specific decisions, (3) Question everything, (4) Learn together, (5) Failure is part of the journey, (6) Open and flexible toolbox, (7) Plan for what you want; start with what you have, (8) Maximise photosynthesis year-round, (9) Minimise disturbance, (10) Harness diversity, (11) Manage livestock strategically. (See Figure 5, below.)

Figure 5. Regenerative principles being applied in NZ

The white paper acknowledges significant overlap between mainstream and regenerative agriculture. Farming is a continuum of practices with no hard and fast distinction between mainstream and regenerative agriculture systems and practices. The white paper assesses the compatibility of mainstream and regenerative farming practices and management strategies. (See Table 5, below.)

Developing specific “regenerative practice” guidance for New Zealand’s many different primary sectors and geophysical contexts is a huge challenge, says the white paper, but one that may be necessary. The current complexity of information or misinformation on regenerative agriculture was identified as a barrier.

Farmer focus groups involved in the research identified ‘mindset’ as a defining characteristic of regenerative agriculture, seeing it as an important factor when working with complex living systems. Regenerative agriculture practitioners appear more likely to question the status quo, and look for new opportunities and different ways of living, working and improving their farming system.

A scientific framework for guiding regenerative agriculture research in New Zealand

Anecdotal evidence for the benefits of regenerative agriculture in New Zealand is growing. Regenerative practitioners are recording their observations and sharing them via social media and on-the-ground, farmer-led events. There is high demand for scientific testing of these observations and reported benefits.

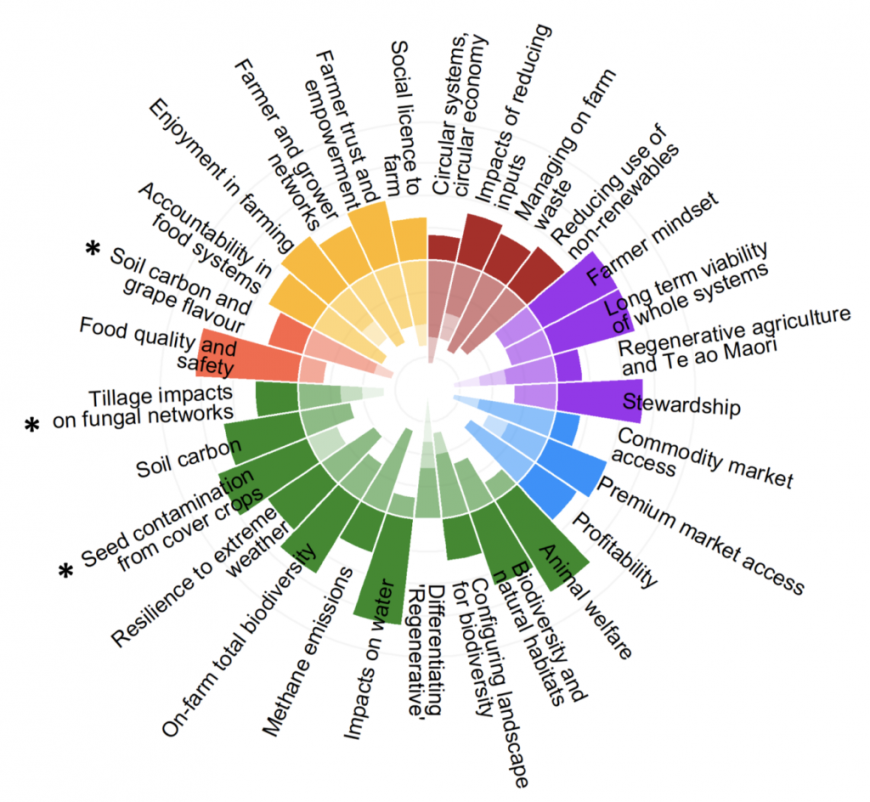

The white paper finds support for 17 priority research topics identified by representatives of the major agricultural sectors in New Zealand, regenerative agriculture practitioners, and professionals in the wider agri-food system.

Representatives of four NZ major primary sectors are asking for research on how regenerative agriculture impacts: (1) Freshwater outcomes; (2) Food quality and safety; (3) Farmer empowerment and mindset; (4) Long-term viability of whole systems; (5) Animal welfare; (6) On-farm all taxa (total) biodiversity; and (7) Soil carbon. They also asked researchers to assess how regenerative agriculture might increase (8) Resilience; (9) Accountability in our food systems and (10) Access to premium/niche markets. (See Figure 11, below.)

Figure 11. Research areas identified as important by 60 participants from 4 agricultural sectors. The relative importance is indicated by the length of the bar segments. Research areas are color-coded by theme

Regenerative farmers highlight the need for scientific studies on how regenerative agriculture affects: (11) Soil health; (12) Profitability and production; and (13) Whole-of-system environment, social and economic outcomes at farm-scale.

Finally, professionals in the wider agri-food system further want: (14) Data to de-risk investment and transition to regenerative agriculture; (15) ‘Conventional-style' practice guides for regenerative agriculture, customised for different sectors and NZ contexts; (16) An understanding of the ‘regen ag continuum’ and (17) Clarity around the need for a definition/certification for regenerative agriculture (or the lack thereof).

Recommendations for research design

The white paper makes several recommendations for regenerative agriculture research design. These include:

- New Zealand soils have a relatively high carbon content compared to many countries at similar latitudes, but soil erosion is a problem. The key questions in New Zealand are: can regenerative agriculture prevent further soil losses, and how and where can soil carbon further increase?

- Research on regen ag pastoral systems must account for nuances in the varied grazing management approaches that underpin all pastoral systems.

- Genuine collaborations with producers (for on-farm outcomes) and brands/marketers (for product claims and consumer trends) could accelerate data-based feedback between scientists, consumers and farmers/growers and result in immediate, highly efficient incentives for behaviour changes among both producers and consumers.

- There are multiple benefits from focusing research efforts on areas or communities where the most gains can be had (eg where drought forecasts are the most extreme; where regulation already promotes rapid change in land management).

- Research should adopt some common metrics to allow comparability of results, including metrics benchmarked and relatable to producers (farmers and growers).

- Research to test regenerative agriculture claims should focus on established regen ag farms successfully managed under regenerative agriculture principles for multiple years, as well as transition case-studies.

- Economic assessments offer limited insight if they do not account for increase or decrease in natural capital.

- Research should prioritise Māori engagement and mātauranga Māori research approaches, if it is to be relevant to New Zealand. For this to be meaningful, such research must be initiated and guided by Māori experts (currently in progress).

- Experimental approaches to test environmental claims should include pairwise comparative approaches with sufficient replication, or large-scale time-series (preferentially 5+ years) across a network of unpaired sites with adequate baselining.

- Combining large-scale methods with large representative samples of population or businesses, and qualitative methods with smaller, carefully selected, representative samples of individuals or businesses, would enable researchers to gain data on the socio-economic attributes of regen ag across a relevant breadth and depth.

More information:

- Regenerative Agriculture in Aotearoa New Zealand – Research Pathways to Build Science-Based Evidence and National Narratives

- Regenerative Agriculture project information

- In-depth topic reports on 13 priority research areas will be released in the coming weeks.

| Mainstream practice or management strategy | Compatibility with regen ag principles |

| Pastoral farming systems | |

| Rotational grazing systems promote perennial pasture growing year-round. | Compatibility with principles 8 and 9 |

| NZ perennial pastures include mixed grass & legume. | Compatibility with principle 10 |

| Compared with much of the rest of the world, NZ rotational grazing systems are world-leading. NZ has some of the lowest greenhouse gas and water footprints per kg of meat, milk and wool globally. NZ farmers also have a reputation for being highly innovative and fast adopters of new practices and technologies. | Compatibility with principles 4 and 5 |

| Set stocking, short rotations or regular severe (low residual) grazing suppresses grass growth and photosynthesis and can also create bare exposed soil between pasture plants. | Incompatibility with principle 8 |

| High rates of synthetic fertilisers common in more intensive systems are considered a disturbance to the diversity and function of the soil microbiome, as are herbicides used for weed control. Tillage for summer or winter forage cropping is a mechanical disturbance, and these tilled forages often receive selective herbicides and pesticides. | Incompatibility with principle 9 |

| Tilled summer crops and winter forage are usually monocultures and incur substantial soil losses. While grass + legume pastures are more diverse than monocultures, the diversity is very low relative to more common regenerative practices where 8 species from 3+ functional groups would be considered low to moderate diversity. | Incompatibility with principles 9 and 10 |

| Arable farming systems | |

| Adoption of no-till arable systems is increasing steadily, while the number of tillage passes has been steadily decreasing over the last 10–15 years (minimise disturbance). | Compatibility with principle 9 |

| NZ arable farmers also have some of the most diverse crop rotations in the world, with the Foundation for Arable Research (FAR) collecting levies across 45 categories and 80–100 different species. Most arable farms have some degree of livestock integration across the rotation, although in some regions the traditional mixed cropping system with longer pastoral restorative phases has become less common. | Compatibility with principle 10 |

| Winter fallow periods have largely disappeared, particularly in the South Island, due to an increase in autumn sowing for winter cover crops (e.g. oats, rape, ryecorn, grass, kale), and catch crops (e.g. oats, triticale) being grown post winter crop grazing events and prior to spring sowing. However, the paddocks are bare for short periods to allow turnaround time. | Partial compatibility/incompatibility with principle 8 |

| Most arable crops are grown as monocultures and weeds are controlled with selective herbicides, which reduces diversity. High rates of synthetic fertilisers are common, as are a wide variety of herbicides, insecticides and fungicides which reduce diversity and disturb the soil microbiome. | Incompatibility with principle 10 |

Table 5. Compatibility of common practices or management strategies employed in mainstream farming systems in NZ with regenerative agriculture principles

Author

Annabel McAleer

Senior Communications Advisor, Our Land and Water